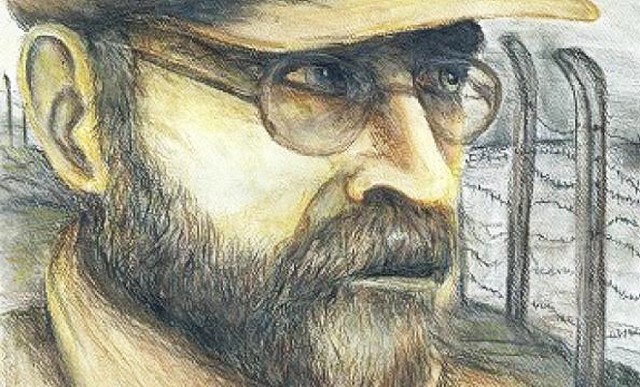

A short overview on the life and the works of Janusz Korczak, doctor, pedagogue, writer.

–

by Lorenzo Berardi

–

The name of Polish author Janusz Korczak is well known all over the world among teachers and students of pedagogy. In Poland, at least four generations of people grew up reading children books written by Korczak. Inspired by works of Swiss pedagogue Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi and Indian writer Rabindranath Tagore, Korczak was an educator well ahead of his times.

In the first years of the 20th century the Polish pedagogue believes that children are entitled to their own opinions and to the same fundamental rights of grown-ups. That’s why a child must be respected just like any other person and put into the condition of exercising their rights by stressing their intelligence and comprehension skills. This is the best way to make children more self-confident and more responsible as well as to establish a peer to peer relationship with their educators. According to Korczak, most if not all problems faced by teachers and pedagogues can be solved by encouraging an active participation of children into activities and not by forcing them top-down to a set of rules. The Polish author and doctor was consistent in following and spreading these beliefs and precepts during his whole life.

Korczak was born in Warsaw in 1878 from a Jewish secularist family. His real name was Henryk Goldzmit, but he chose the pen-name of Janusz Korczak for the first time as a 20 year old, when he took part to a literary contest. He studied Medicine first at the ‘Flying University’ (as Russian occupiers had banned academic education) and then enrolling to the University of Warsaw. In those same years Henryk aka Janusz is also a brilliant reporter and a writer of short stories. One of his early reportages Dzieci ulicy (The Children of the Street) is even included in an anthology of Polish non-fiction throughout the 20th century compiled by journalist Mariusz Szczygieł (and not yet translated into English.) Even though he’s a pediatrist working for a children hospital in Warsaw, Korczak takes part to the Russian-Japanese war as a field medic in 1906. He will be again on the battlefield, this time in the ranks of the Polish Army, during World War I.

The Warsaw Years: Dom Sierot and Nasz Dom

However, children – and particularly orphans – are those the young doctor always returns to. In 1911, Korczak is back in Warsaw where he opens Dom Sierot a revolutionary orphanage for Jewish children that he runs as a volunteer director. Dom Sierot lies at number 92 of Krochmalna, the same street where soon to be famous Yiddish author (and Nobel laureate in Literature) Isaac Bashevis Singer lives in those years. The orphanage conceived by Korczak is like no other in the world. It is organized as a mini-republic of children boasting its own parliament, courthouse – whose trials and verdicts will be more than once about the director himself – and a weekly gazette. The latter, called Mały Przegląd (The Little Review), is issued with a popular Polish-Jewish newspaper printed in the capital and open to children contributors from all over the country. Some of the kids submitting their articles to Mały Przegląd will survive the war to become reporters. In 1919, Korczak’s commitment to children redoubles: together with Maryna Falska and Maria Podwysocka the author opens Nasz Dom (Our Home), his second orphanage in Warsaw, this time for children coming from Catholic families.

All through the 1930s, Korczak becomes ‘The Old Doctor’ on a successful programme broadcast by the Polish National Radio. On air the author talks about education to children and their parents making sure to speak in a colloquial language that even the little ones can understand. The programme keeps a staggering popularity for many years in a row with thousands of Polish families listening to it and many kids writing letters to The Old Doctor who replies in person on the magazine Antenna. The last time Korczak goes on air is just a few hours before the Polish National Radio is silenced by the Nazis on 23rd September 1939 during the siege of Warsaw.

Five days later the German troops enter the Polish capital and promptly occupy the Dom Sierot orphanage on Krochmalna Street. Janusz Korczak and his children are forced to move to much smaller premises within the soon-to-be-built walls of the Warsaw Ghetto. Throughout the following three years spent inside the oppressive, overcrowded and famished cage of the Ghetto under hygienically conditions getting more and more appalling, Korczak doubles up his efforts looking after the kids of two orphanages at the same time. Hard and demanding times that the author recounts in the poignant but clear headed pages of his ‘Ghetto Diary.’ The Polish underground, aware of Korczak importance, kept on offering the director of Dom Sierot an escape plan to the ‘Aryan side’ of the city. However, the author always refused to leave his orphans to their bitter fate, perceiving the doom awaiting them.

In August ’42, the Germans decide to get rid of the dozens of thousands of people still living in the Ghetto by dispatching them to sure death in the extermination camp of Treblinka. Soon enough the almost 200 children of Dom Sierot are taken from the orphanage and marched by Nazi soldiers to the Umschlagplatz. Many people gathered there or along the streets of the Ghetto witness this last march and Władysław Szpilman mentions it in his memoir ‘The Pianist’. Korczak told the kids that they were going to have a countryside trip and asked them to dress themselves up for the occasion. Some witnesses claim the children, led by the Old Doctor himself, marched all together following a huge flag, holding their hands and lined up in twos. It’s a warm and sunny day when they embark on their final journey to dreadful Treblinka. None of them will ever come back.

The legacy of the Old Doctor

Seventy-six years later, what Janusz Korczak has left us is 23 books and about 1,500 articles. His writing encompass many genres from children books to essays passing through the answers he wrote to his young listeners, letters and diaries. To this day his pedagogical works are still seminal for teachers and educators all over the world thanks to foreign translations and reprints. As for the books of fiction Korczak wrote for kids, they show a world of grown-ups in all of its pros and cons from a young person perspective hence empowering children to make it a better place.

Korczak’s most successful book – the internationally acclaimed ‘King Matt The First’ (Król Maciuś Pierwszy) – published in ’23, reads modern to this day. The story sees an 8 years old child becoming king all in a sudden upon the death of his father. Whereas some court dignitaries would dismiss the princeling as an infant and treat him as such, Matt doesn’t want to be a puppet and gains awareness of his new position. King Matt is willing to become a reformer by trying to give equal rights to grown-ups and to kids, but can’t quite accomplish what he has in mind. However, little Matt learns from his failure and understands how he has to become more humble, less impulsive and more forgiving to gain the experience he needs to run his own country. There’s also a sequel to this book, entitled ‘Little King Matty…and the Desert Island’ (Król Maciuś na wyspie bezludnej) which has been translated into English only in 1990, but can even boast an Esperanto version published in 2009.

In 2010 the Polish Book Institute (Instytut Książki) bought the publishing rights to the complete works of Korczak and started printing or reprinting all of his works, both in Polish and in foreign translations. Even though some of Korczak books had run out of print for some time, Poland has never forgotten him. In 2012, seventy years after the Old Doctor’s death and one hundred years after the foundation of Dom Sierot, a string of events, exhibitions and meetings were held focusing on Janusz Korczak and his legacy. Today those who walk around Warsaw, birthplace of the author, can see two monuments honouring the famous pedagogue and his children. One of them lies next to the former orphanage of Krochmalna Street (now Jaktorowska Street nr. 6), while the other is in the Świętokrzyski Park in central Defilad Square.

In 1990 two world famous Polish filmmakers, Andrzej Wajda and Agnieszka Holland, directed and wrote respectively ‘Korczak,’ a poignant movie on the Polish author with a score by Wojciech Kilar. It’s masterful cinematography shot in black and white and it delivers a believable portrait of the Polish humanitarian insisting on his willingness to help the others, inner strength and determination to face adversities (without downplaying the pedagogue’s stubbornness.) Not everyone agrees on the ending of the movie that may be seen as too soft and peaceful given what happened to Korczak and his orphans. However, Wajda and Holland’s take of this tragic last march to Warsaw’s Umschlagplatz matches with what Władysław Szpilman wrote about it in ‘The Pianist.’

“You can’t leave the world as it is” warns one of the most famous quotes by Janusz Korczak. And the Polish pedagogue kept true to his words thanks to his noble actions as well as to the books he left behind. Korczak was one of the very first educators to understand children are little grown-ups and, as such, are entitled to express their own opinions and to have most of the same rights. His goal was to stress how childhood is not only a time for playing and discovering, but also an essential time for learning about a wider world and how to make it better and more just. What grown-ups should be more aware of, Korczak tells us, is that children are functioning human beings with their own dignity, their own sensibility, and their own opinions. Listening to those opinions without dismissing them as childish plays a crucial part in understanding children and their feelings. Just like grown-ups, kids can sometimes make mistakes, but they have the right to learn from their own errors and oversights in order to become men and women.

The legacy of Korczak can be found reading the Convention of the Rights of the Child adopted by the United Nations in 1989. The 54 articles of this treaty prove that the memory of the Old Doctor and his children is still alive and shall never be forgotten.